It’s been a week since Discovering Collections, Discovering Communities, the Jisc conference (in partnership with The National Archives and The British Library), on the theme of “Radical reimagining: interplays of physical and virtual”. Held in the beautiful city of Durham, the conference was three days of jam-packed talks, panels, and workshops exploring every aspect of the GLAMA sector.

Putting together a highlight reel was an impossible task for such a fantastic array of talks, so please find below my summaries of the ones I listened to, in order of attendance.

Keynote 1:

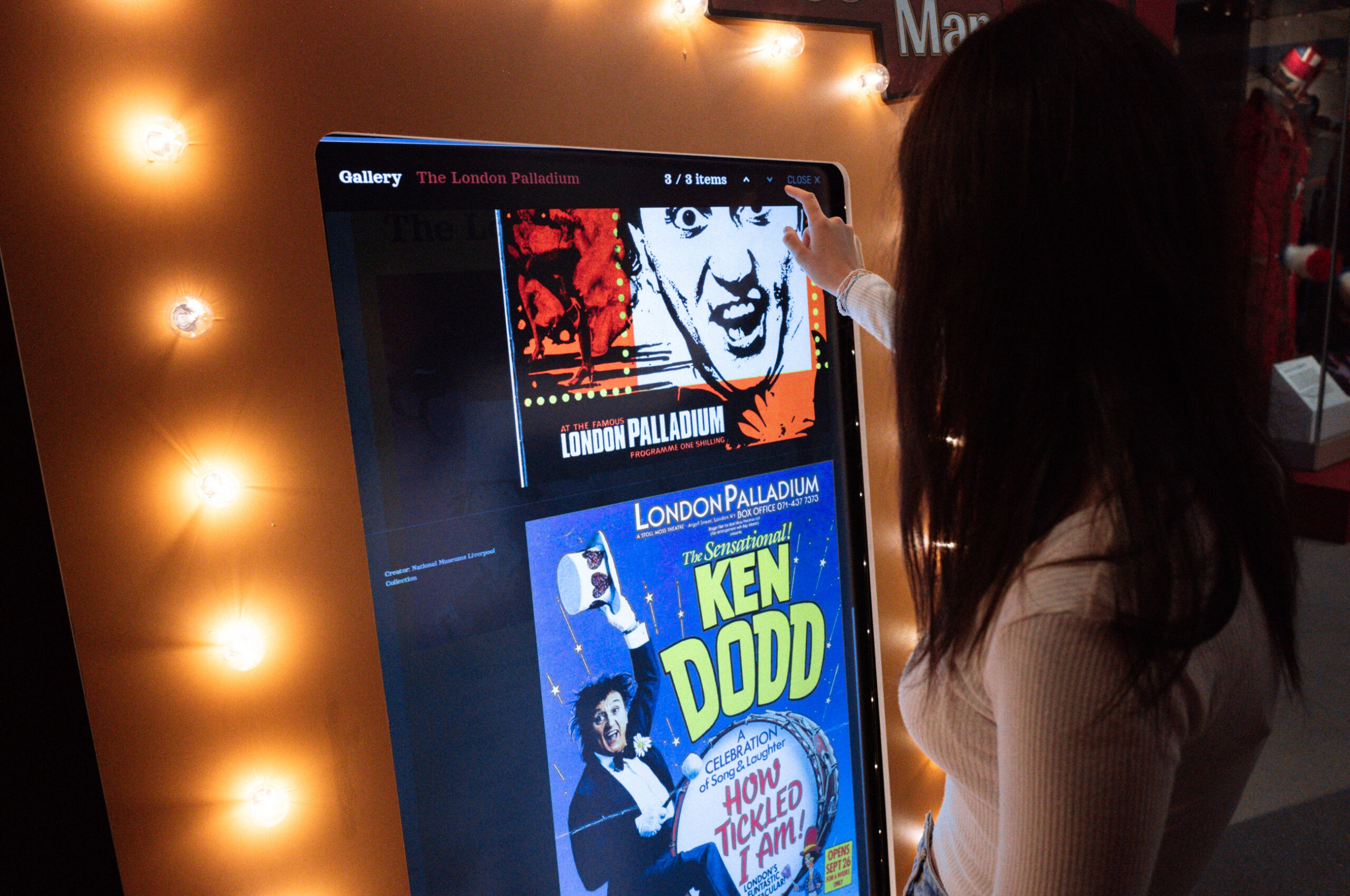

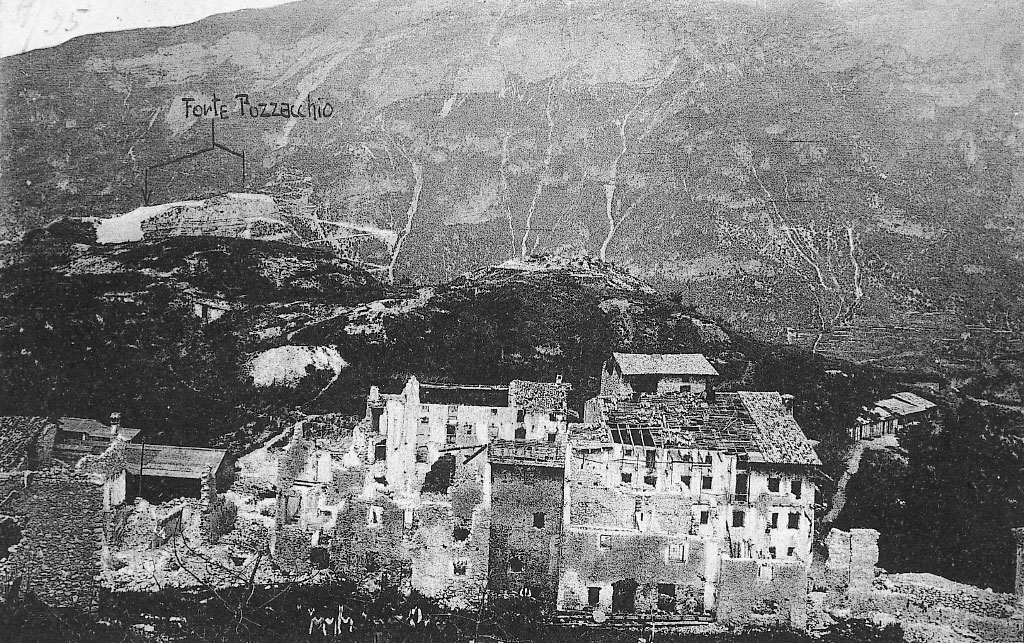

Sheffield Hallam University’s Professor Daniela Petrelli’s keynote “Designed to Generate Emotions: Taking Museum Visitors Beyond Information” was an excellent start to the week. Daniela talked about the often fraught, sometimes love/hate relationship between museums and tech that dates back to the 90s, and gave several examples of uses of tech in museums. The interactive exhibits at Fort Pozzacchio and Chesters Roman Fort are two particularly fantastic examples of how tech and interactivity can be used to turn museum visits into bespoke, multimodal experiences that mix materiality with the digital sphere.

Panel 1: Engaging Communities, Opening Collections

Argula Rublack of the Senate House Library gave a talk on co-creating digital experiences. Argula spoke about the Haud Nominandum archive, which was donated to Senate House by Jonathon Cutbill, owner of Gay’s The Word – a gay bookshop in London which was targeted by the police under gross indecency laws in the late 1970s. She also spoke about the ongoing Guyana project, a joint initiative between Senate House Library and Guyana SPEAKS, a movement that seeks to bring the Guyanese diaspora together and highlight their unique contributions to art, history, and culture. The key takeaway from this lecture is that while flashy digital deliverables are often the part of a project that gets the attention, the true work that goes on takes place behind the scenes and involves creating lasting relationships with the communities the archive/library/museum wants to connect with. Her ending note, that institutions learn just as much if not more than the communities they work with, was especially apt.

Susannah Gillard, Content Specialist and Archivist at the British Library (BL), then spoke on their developing relationship with the Qatar Foundation Partnership. The aim is to make the BL’s collections available to people in Qatar. This touched on a lot of issues – user experience, translations and language barriers, copyright, outdated and offensive language in British museum collections – but her line of argument regarding the need for such partnerships to have a “conscientious bilingual framework” was especially interesting. The output of the project is being made freely available via the Qatar Digital Library.

Fiona Graham and Paul Ottey (from the University of Staffordshire) gave a brilliant talk on the intersection between film practice as actual research and digital preservation. Fiona and Paul had been deeply embedded in a local heritage project in Cambrai, France, which saw a First World War tank (named ‘Deborah’) that had been excavated and housed in a barn in France moved to a purpose-built museum in the nearest town. Their film of this process, based on ethnographic techniques, explored the deep level of engagement the community had with this piece of hidden history.

Panel 2: Digitally Mediated Encounters

Next up, Eilidh Lawrence told us about the unfolding Re-collecting Empire project at the Museums of the University of St. Andrews. This project seeks to re-examine Britain, Scotland, and St Andrew’s historical and contemporary links to the colonialism and its lasting legacy on every scale, from the international to the local. This project involved virtual reality (VR), augmented reality (AR), and app-based experiences, all co-mingling with the physical space and evolving alongside the scope of the project.

The use of VR in museums and heritage spaces is promising and an amazing experience…for some. However, for those with glasses, headwear, inner-ear or balancing issues it can come with a host of issues. The complicated tech needed is a barrier to entry, and there is also time and effort cost to monitoring guests using VR. While VR was an interesting avenue to explore, Eilidh concluded that, due to the tech being in its infancy, it isn’t yet viable as a standalone strategy. AR tech on phones or tablets is more common, lowering the barrier to entry, and far less likely to make a museum guest walk into a wall. The app-based experience, which used Smartify, was simpler still. Eilidh concluded that in terms of usefulness and relevance to the exhibit, the app ranked above AR which ranked above VR. Predictably, navigating the actual physical exhibit ranked highest amongst guests in terms of ease of use, but the different digital aspects of the project were very well-received. You can learn more about what the Museums of the University of St. Andrews by checking out their website and giving them a follow on Twitter at @MuseumsUniStA.

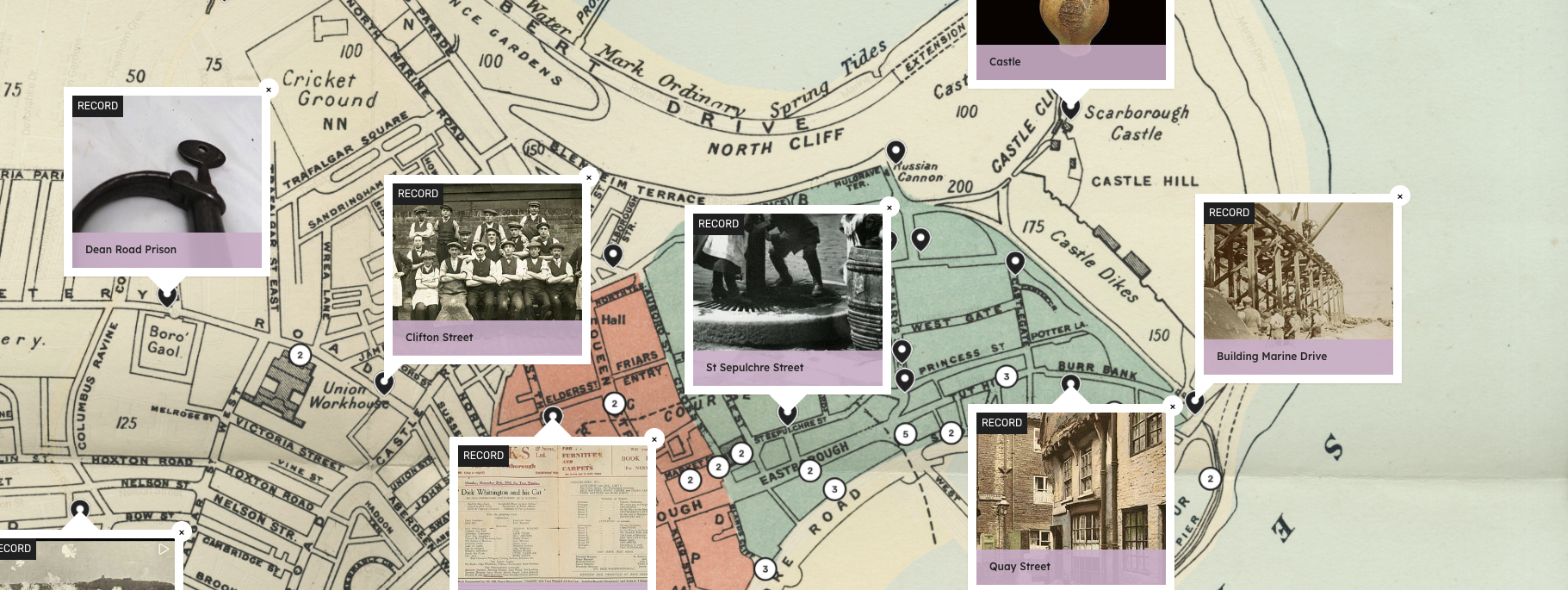

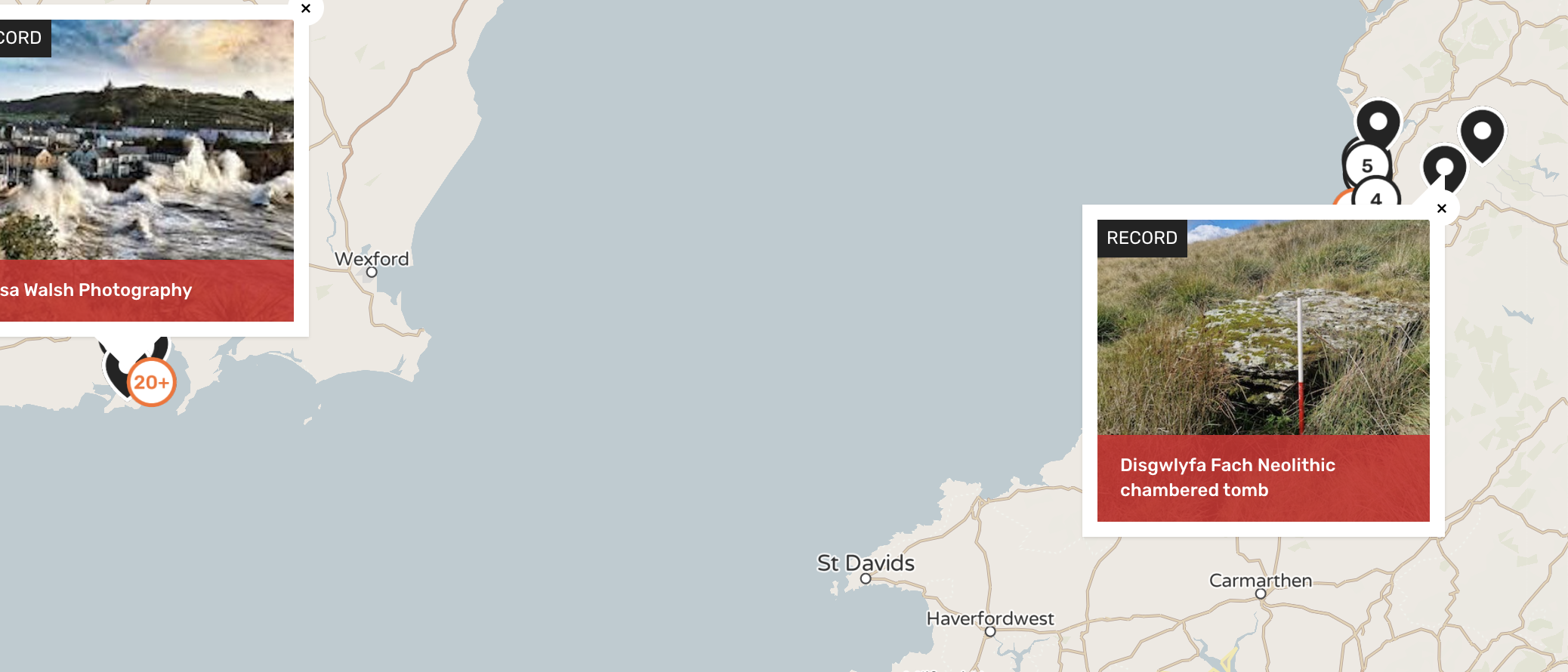

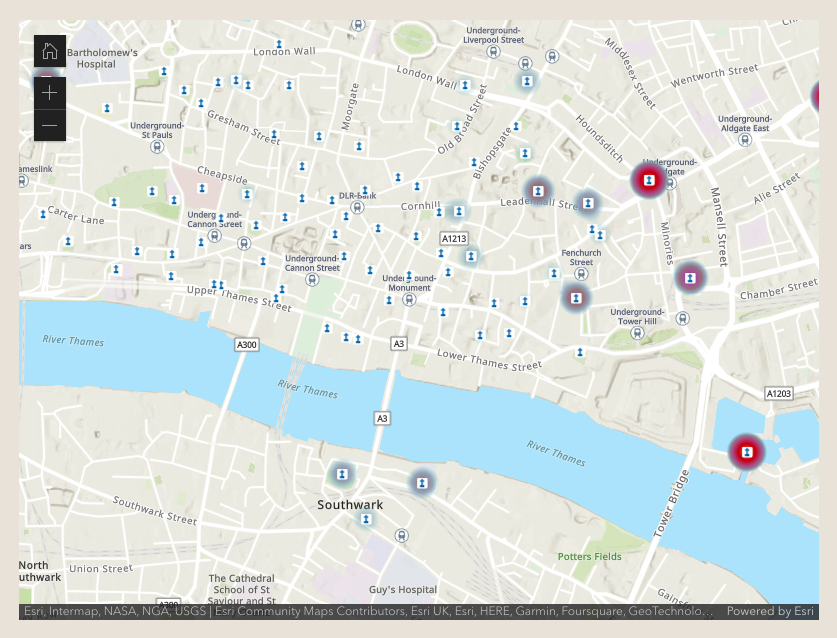

Next up was a talk given by Dr’s Olly Ayers & Andrea Kocsis, professors at Northeastern University, London, on the Unforgotten Lives exhibition and the Mapping Black London project. Both academics worked closely with members of the local London community to engage stakeholders and create interactive, multimedia exhibitions which explored the lives and legacies of Black Londoners and works to undo the narrative that, pre-Windrush, London and Britain more generally did not have a vibrant Black community. Focusing both on putting the lives of famous pre-Windrush Black Londoners (for example, Ignatius Snacho) in context and highlighting the stories of ordinary Black Londoners, these projects mixed records (material temporal) with maps (digital spatial) and the app (digital-material spatial) to create personalised, specific, and flexible learning experiences for their audience.

Rob Chipperfield, the Digital Content Officer at The National Archives, gave a talk on the unique challenge of using a digital-only resource to engage a physical audience. The 1921 census release was a huge opportunity to get people into the physical space of the archive, but the actual documents were only available through screens. Through engaging with local businesses and organising community days and community competitions, Rob & the team were able to introduce huge swathes of the public to the archives and get them engaging with local census history.

Keynote 2:

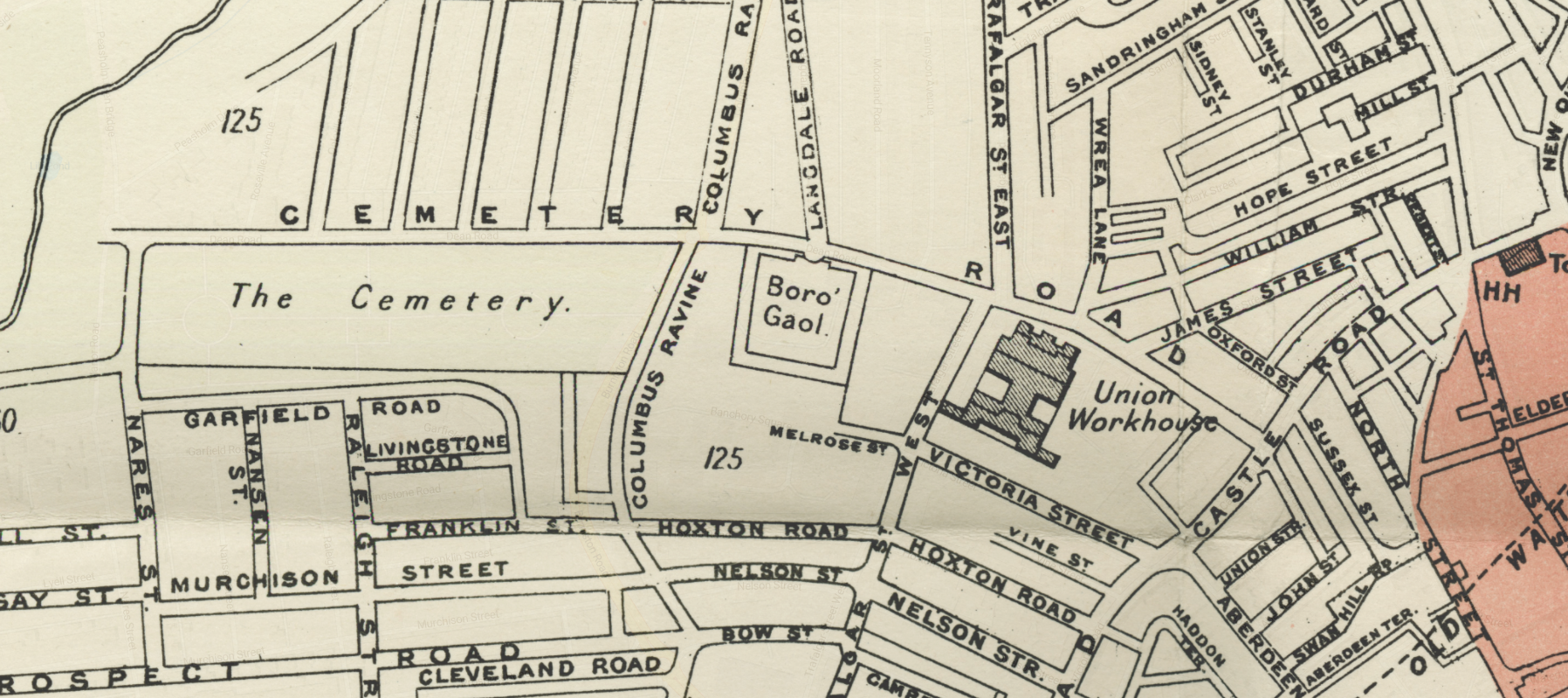

The next talk, “Artificial Interactions? Digital resources, cultural heritage, and the rise of AI.” was from Profesor Claire Warwick, a Professor of Digital Humanities at Durham University. Her talk focused on the startling ubiquity of artificial intelligence (AI), seemingly now in every sector of human endeavour. She touched on the evolution of knowledge exchange from monks writing on precious vellum to Microsoft Excel, of horses from necessary for economic survival to pampered pets, and of how maps communicate temporal data on a spatial format.

Keynote 3:

Ojoma Ochai (LinkedIn) is the Managing Partner of The Creative Economy Practice at CC Hub. Her talk, “Tech applications in the creative industries in Africa”, was another highlight of the conference. She spoke at length about the vibrancy of the creative economy on the African continent and gave several examples of creative and cultural businesses and innovations taking place. She also touched on the responsibility for people from the Global North to be mindful of recreating old stereotypes and lies, and of flattening the vast and diverse African continent into a two-dimensional single “Africa.” She argued that there can be no reimagination without decolonisation, and that there is a great need to decolonise knowledge exchange and no longer relegate Africans to being subjects of research only. Equitability is central, and she ended on the promise that “we will decolonise memory.”

Panel 3: Learning in Virtual and Blended Environments

Hannah Nicolson, the Education Officer at Lloyd Banking Groups Museum on the Mound delivered a fun, tactile session on how she uses materiality to teach children about money. Owning that money and finance history can be a little dry, she talked us through the high-energy, blended learning sessions she delivers for schools all over the country. She concludes that while digital engagement strategies are necessary and often brilliant, nothing beats tactile learning and materiality in the classroom. Even over COVID when they could not physically visit different classrooms, Hannah and her team were mailing out physical items to be used in a workshop where they dialled in virtually – innovative!

Erum Hamid, the leading Library Assistant at the British Library, discussed how virtual makerspaces can be used to reconnect us with the physical. Especially post-COVID, many traditionally physical or material-based activities in universities and libraries turned digital. Erum’s talk explored the tensions, pros, and cons of the digital turn and asked about the possibilities for interplay between virtual makerspaces and physicality.

In “Where is the awe? Building personal connections with collections, no matter the medium” Vicky Price, Head of Outreach at University College London Special Collections, explored the ways in which she uses UCL’s gigantic collection to connect with children. She stressed the importance of nurturing open and creative environments and meeting the learners where they are, building up to the end result: a feeling of shock and awe that connects that person to the gravity of the archive and the histories they are experiencing.

Keynote 4: Curating Future Stories: Digital Objects and Data Heritage

The final keynote of the conference from Dr. Chiara Zuanni (Assistant Professor in Digital Humanities at the University of Graz) focussed on data heritage and the creation of digital content. She argued that while a huge amount of digital content had been created, this is not the same thing as having a digital strategy. Many a museum or academic had spent a huge amount of time and money on creating digital resources only for them to be rendered unusable by time, lack of funds, or a change in software. She also spoke about personal digital archives, such as Facebook and other social media giants, and the ways in which collecting memory and knowledge during the pandemic had no universal format or standard. She ended on the note that the way we collect data now will shape the understanding of our present moment as history, asking the audience to consider the gravity of that responsibility.

The conference was absolutely fantastic. As a representative of a private sector it was a brilliant opportunity for me to sit back and listen to what the people we support (academics, archivists, engagement officers etc) need and want from their sector and ours. The key concerns repeated to me were about digital sustainability, questions over ownership, and the central issue of how to make access to digital heritage as equitable and democratic as possible.

I’d like to thank Jisc, The National Archives, and The British Library for putting on such a brilliant event with so many fantastic speakers. Looking forward to the next one!